|

|

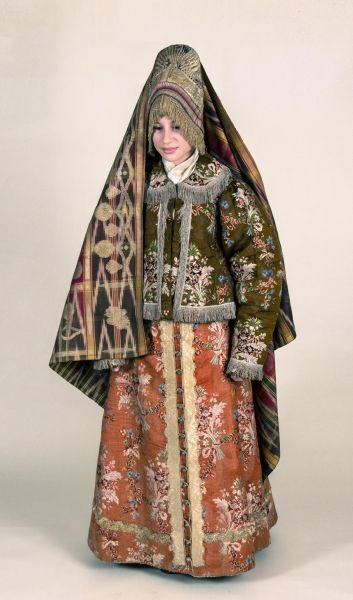

Female Festive Costume. Sarafan. Late 18th – early 19th century

Brocade, lace, gold lace

136 х 445

State Russian Museum

Пост.: 1938 из ГЭ

Annotation

Shugai. First third of the 19th century

Brocade, metal fringe. 55 x 143

Qanawat Veil. 18th century

Silk, gold threads, weaving. 212 x 121

Kokoshnik. 19th century

Brocade, galloon, silk ribbons, gold fringe. 28 x 30

Russian national dress always attracted artists because of its brightness and originality. The makeup of a set of rich festive clothes was almost identical throughout all the lands of Muscovite Russia, and later of the Russian Empire. Before Peter the Great it was seen mainly in the milieu of boyars and grand dukes; in subsequent times it became the property of the urban population and of well-to-do peasants.

The Kokoshnik was a festive head-dress worn by women, and its shape indicated the region that it came from. Kokoshniks were worn by peasant women, women living in towns and the wives of merchants. Vertically elongated head-dresses (as in the painting Russian Girl by Carl von Wenig) were typical of the Kostroma Province. They were decorated with small, tightly-packed silk ribbons and gold fringes, and the upper part of a Kostroma kokoshnik spread out in a fan of small pleats. Women in the Tver Province (as in Korzukhin’s painting Hen Party) wore a cylindrical kika with a flat underside, and their head-dresses glittered with gold and pearl embroidery.

An essential part of both everyday and festive clothing was the sarafan, a long woman’s dress that hung down from the shoulders. From the time of Peter the Great onwards people began to think of the sarafan as something worn by women from the common people or by merchants’ daughters, and it was only with the start of Catherine the Great’s reign that the fashion for sarafans became established again at court. The decoration of sarafans, with filigree buttons, gold braid and silk ribbons, turned this dress into something that was truly precious, and a family’s prosperity could be judged from the decoration and the buttons of such a dress.

Women’s festive dresses were quite often finished off with a shugai, an outer jacket with long sleeves and either with or without a large collar. The shugai was for festive occasions and was sewn from valuable materials such as damask, velvet and brocade, and was then decorated with silk ribbons, braid and fringes.

At the end of the 18th and into the middle of the 19th centuries an item of clothing that marked out women from the ordinary classes was the fata, a head covering that, depending upon prosperity, could be made either from cheap material or from costly material embroidered with gold thread.